A project to restore the memorial of lynching victim Commodore Jones

by Kipton Moravec, kip@kdream.com

DGS 2021 Writing Contest Submission

In April 2019, 34 members of the Episcopal Church of the Transfiguration in Dallas went on a civil rights pilgrimage through Mississippi and Alabama. Besides seeing the famous places like Selma and Birmingham, we stopped at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama. It opened to the public on April 26, 2018 and is the nation’s first memorial dedicated to the legacy of enslaved Black people, people terrorized by lynching, and African Americans humiliated by racial segregation and Jim Crow.

Photo by Kip Moravec

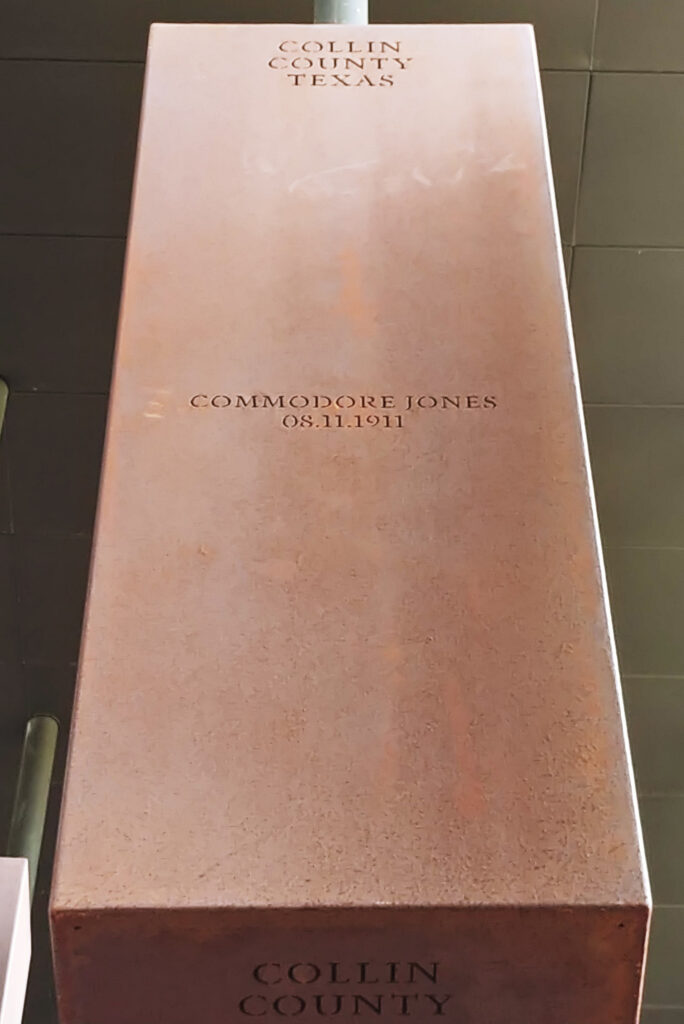

The Memorial structure at the center of the site is constructed of over 800 corten steel monuments – one monument for each county in the United States where a racial terror lynching took place. The names of the lynching victims are engraved on the columns.

Since I lived in Collin County, Texas, I searched out the column for Collin County, and found it. It had one name, “COMMODORE JONES 08.11.1911”. I pulled out my phone a did a quick Google search and found a web page with three newspaper articles about his hanging in Farmersville, Texas for being rude to the telephone operator over the phone. I was curious to find out more about Commodore Jones.

Photo by Kip Moravec

When I got home I did some more searching and found the name on the Findagrave.com website, I now knew he was buried in Royse City Cemetery, and I had a birth date, December 22, 1884. But that was all I could find. Internet searches found nothing else.

I am very active in amateur radio, often helping with communication at many public events. I was assigned to work at a water/rest stop in Farmersville for a bicycle rally charity event. The rest stop was at the “Onion Shed” on Main Street in Farmersville. I met Licea Caspari, who was on the city council at the time, and she knew about the lynching. She walked me down to Main Street and pointed to the corner of Main Street and McKinney Street, at the southeast corner of the square. That is where the old telephone office used to be. Licea was interested in the lynching also and asked to keep in touch.

Photo by Kip Moravec

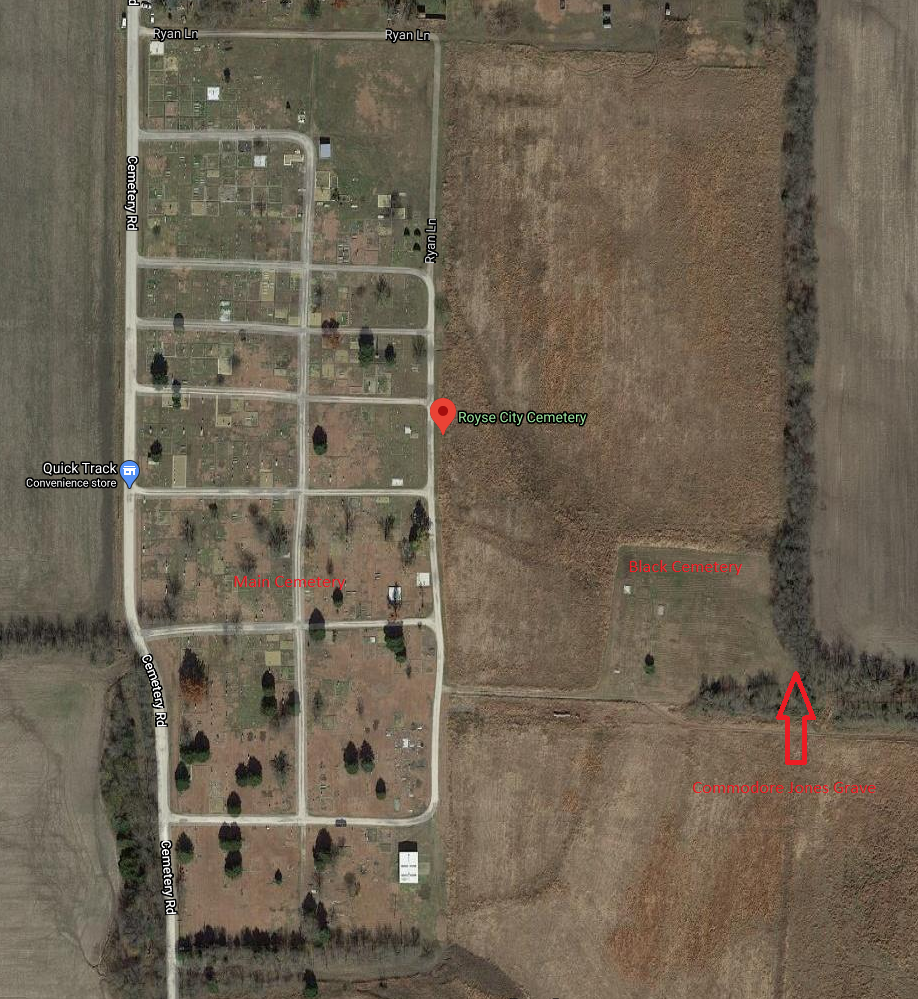

One Sunday at church, Alan Justice and I were talking about our pilgrimage and Commodore Jones, and we decided to head to Royse City after church to find the grave. We searched and searched the cemetery and could not find the headstone. The cemetery is kept in pretty good shape, and it looked like there was an older section and a newer section. We walked back and forth and could not find anything. We got back in Alan’s car and were on the “street” farthest back (east). Beyond it to the east was unmowed field and then a hedgerow with trees separating the cemetery from a farmer’s field. We happened to notice a white cross sticking up through the weeds way back to the east. Maybe that was the Black section of the cemetery. We turned around and followed the road and discovered a mowed lane heading east. We followed it and found another section of the cemetery a long way back from the rest of the cemetery. And way in the back, all by itself, we found the grave of Commodore Jones.

This satellite view of the Royse City Cemetery (north is up). The red arrow points to where we found the grave of Commodore Jones. It appears it is so close to the border of the cemetery they had to bend the hedgerow around the grave site. The headstone was in 3 pieces. The concrete foundation had tilted and the other two pieces were separated. The headstone was facing more south.

I had been trying to get some kind of memorial service or prayer service for Commodore Jones so he would not be forgotten. I had tried to reach out to the two Black churches in Farmersville to see if they had any history about Commodore Jones or wanted to participate in the service. But August 11, 2019 did not work out and it was suggested to try for February 2020 during Black History Month. Due to the COVID pandemic plans were canceled.

Activity on Commodore Jones had come to a standstill. We did not know of any family. We did not know anything else about him.

Our church started a Racial Justice Ministry and they knew of my research into Commodore Jones. We decided to have a grave side prayer service on August 11, 2020 for Commodore Jones. I think we had about 10-12 people attend with 2 priests, and we tried to have a Facebook live showing of the service but after about 10 minutes the phone overheated and that part was over. Our Director of Youth and Outreach Ministries, Dana Jean gave a little sermon and wrote up the experience in her blog.

That blog writeup started things happening. It got picked up by Google’s eNews and some students at Collin College saw it. The Alpha Mu Tau chapter of Phi Theta Kappa Honors Society at Collin College chooses a service project every year and this year they are focusing on the connection between lynchings and police brutality. As part of their project they are hoping to put memorials/markers at any sites where someone was lynched in Collin or Dallas counties. They contacted her and Dana gave them my contact info.

Within a day or two a Professor of History at Collin College contacted Leaca in Farmersville about Commodore Jones. He wanted to add information about the Jones Lynching in his history course. So she put him in contact with me.

A friend of Dana Jean started doing some genealogy searches and found he was listed in the 1910 Census. From that we know he was living with the Carver Family, in Farmersville as a servant and he could not read or write. The other members of the household were Henry L Carver (43), Mattie Carver (40), Sadie Carver (18), Lillie M Carver (16), Grace E Carver (15), Leona C Carver (12), Mattie L Carver (3) and Marjorie W Carver (0). We could not find Commodore Jones in the 1900 or 1890 Census in Collin County, so we do not know where he came from. There is still a large Carver family in Farmersville, and Leaca knows some of them. She is looking to see if there is any family history about Commodore Jones.

We also found out there was no death certificate for Commodore Jones in Collin County. I talked to a lady at the County Clerk’s office and she was going to check with the state to see if one was filed with them from somewhere else.

I also got the name of the President of the Royce City Cemetery Foundation, David Crenshaw, and asked if it would be okay to repair Commodore Jones’ headstone. He told me that part of the cemetery was managed by The New Hope Baptist Church which was about a block from the cemetery. I sent an email to Rev. Grays explaining who I was and a little about Commodore Jones. The following Sunday my wife wanted to visit the grave as she had not seen it. As we passed the New Hope Baptist Church, we saw someone standing outside, and stopped to ask about the cemetery. He went in and got Rev. Grays. He had not seen my email until that morning, and did not know anything about Commodore Jones, or know about any family in the area. He gave me permission to fix the headstone.

I pulled all my information together and made a Zoom presentation to the Phi Theta Kappa Honors Society and the professor interested in Commodore Jones on early in September. I had also set a date of October 3 to fix the headstone. I was worried it would be too hot if we did it any earlier.

I searched the Internet to find out how to clean headstones. The best recommendation was to use a soft bristle brush and water. The Honor Society said they would take care of it.

David Crenshaw recommended getting a backhoe to help resetting the foundation. That would cost about $300. Lecia and my church paid for the rental.

On October 3, I threw shovels and rakes and anything else I could think of into the truck and headed to Royce City. We had three people from my church, five people from Farmersville, three people from the honor society, and David Crenshaw and his brother from the cemetery. A pretty good size crew. We were all masked and practiced social distancing.

However David was running late. The truck with the backhoe broke down on I-30. We decided to see what else we could do. We were able to lift the headstone to the tailgate of the truck where it could start to be cleaned. Then we dug out the base and got it so it could be cleaned also.

The foundation was another issue. It was deep and probably about 700 lbs. Since the backhoe was not there we dug around it. I had thrown two 8’ 2×4 in the truck and we were able to roll it out of the hole by using the 2x4s as levers. About that time the backhoe arrived.

We made the base of the hole as flat as possible, and mixed cement a bag at a time in a wheel borrow and poured it in the hole. After 4 batches we reset the foundation in the hole. The new concrete was about 6 inches below the dirt line so it would not be seen after we filled it back in. The bottom was much bigger than the original foundation so we hoped it would not move for another 100 years.

Photos by Kip Moravec

There was some excitement from the Honor Society. The base had an inscription on it that we had not seen before the cleaning. “Peaceful be thy silent slumber, Placed in thy grave so low, Thou canst never join our number, We will meet on earth no more.” We could not find that exact saying on the Internet, but it is a slight variation on the words from a hymn.

David and his brother put a metal rod into the headstone, base, and the footing. So if it does lean in the future it will not come apart like it did this time. Figure 6 shows the finished headstone.

We still have lots of questions. Where was Commodore Jones born? Can we find him in the 1900 or 1910 census? Does he have any brothers or sisters or surviving family? Who had him buried in Royse City? As it is just outside of Collin County, was he placed there to prevent future incidences? Who paid for the expensive monument? Any help would be appreciated.