Alternative Methods for Researching African-American Genealogy

By Shreeya Madhavanur, Staff

Remembering Black Dallas, Inc.

The advent of databases like 23andMe and Ancestry.com has produced a revolution in genealogical tracing, allowing people to look into their family histories with remarkable ease. This data, however, is not equally accessible to all groups looking to trace their lineage; decades of slavery and institutionalized discrimination have systematically broken family bonds, resulted in large scale displacement, and produced massive historical holes in records of African American ancestry. Thus, the process of tracing black genealogy requires pursuing novel and often complex approaches that are not necessary when researching mainstream, digitized, and thoroughly documented white genealogy. Over the years, these methods, although not without their challenges, have matured adequately to bridge some of these historical gaps, allowing African Americans to explore their roots and celebrate their heritage.

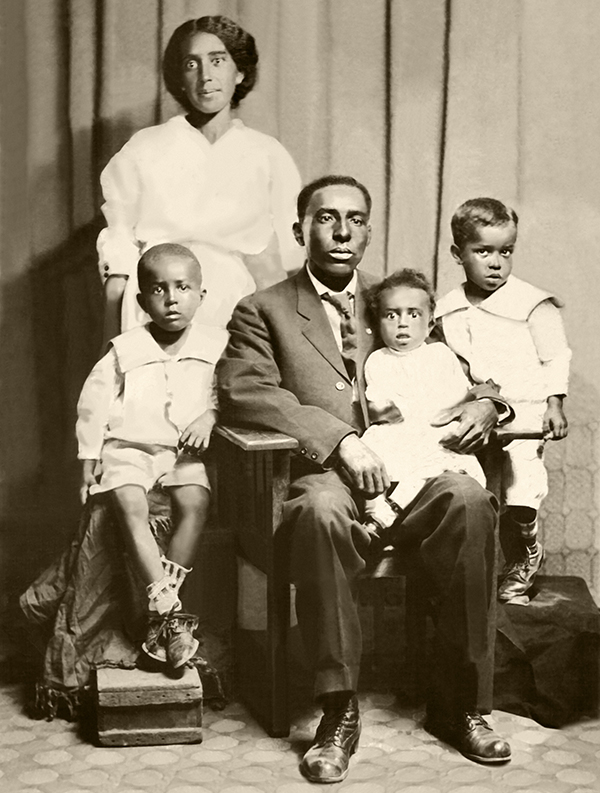

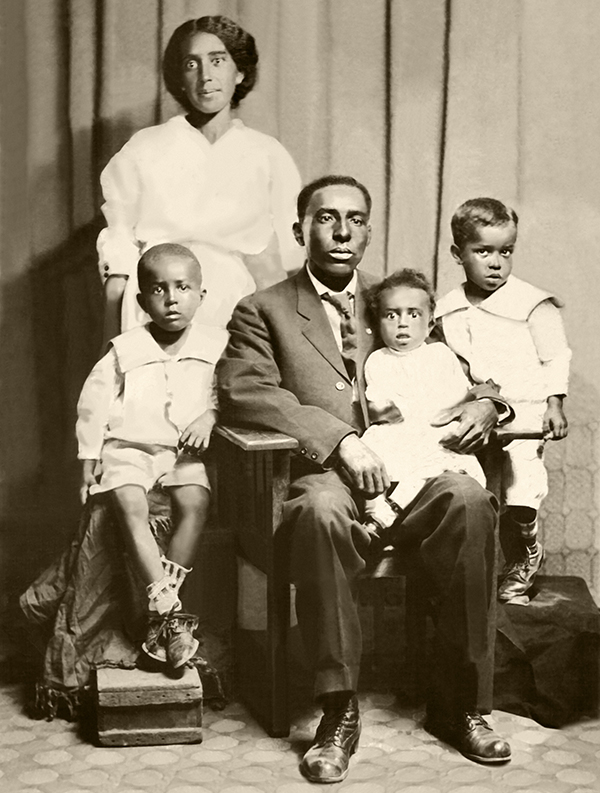

Parents: Berdie Turner Fields and George Fields

Children L > R: James, Audry, Agusto

A commonly used method in studying African American history involves investigating various forms of public records–particularly early census records, which include details that can easily be used to identify a person of interest, including their name, age, and location. Early city directory records contain similar information, such as age, marital status, race, and addresses. Census data additionally yields family listings, which means that finding just the name of a single family member allows one to discover the identities of extended family members to add to the family tree.

Still, African Americans were not identified by name until the 1870s census, so using census data to trace black genealogy in prior years is extremely challenging. Similar information can be found in the extensive Freedmen’s Bureau records, over 3.5 million documents detailing the experiences of black Americans during the Reconstruction period. But because of pressure from white legislators from the South and terrorist groups like the Ku Klux Klan, these records were collected only between 1865 and 1872.

In order to study earlier years, historians often rely on deed data. Today, deeds are generally

thought of as legal documents that affirm ownership of assets such as land, but during slavery times, such deeds contained detailed records of the buying and selling of enslaved African American people. Thus, one can look to the courthouse deed records of slaveholders for a bill of sale or a will containing an enslaved ancestor’s name.

Civil War-related records contain a treasure trove of information. For instance, in order to rejoin the United States post-Civil War, various southern states had to meet certain requirements, including registering African American men over the age of twenty-one to vote. So the 1867 voter registration records can be used to trace African American family histories prior to 1870. Another Civil War-era resource is the pension application files of African Americans who fought on both sides of the war. To back up one another’s pension claims, comrades would often write affidavits for each other that contained more information about a filing ancestor than was required. Further information can be uncovered about an ancestor by ordering a service record from the National Archives. Investigators can research names and regiments by using the Online Civil War Indexes, Records, and Rosters website.

Finally, one can look to the major early black newspapers of the nineteenth century such as Freedom’s Journal and The North Star, as well as genealogically advantageous papers such as The Florida Tattler, The Chicago Defender, and the Advocate (Kansas City, Kansas) to find information on ancestors. Unfortunately, many such records haven’t survived, and those which have are often sparse and not very thorough.

Religious records are another useful tool in black genealogy research. Even before the Civil War, many church membership records included documentation of black members. In fact, prior to emancipation, Catholic Church records in Louisiana (among other states) listed enslaved people by name. Furthermore, churches kept detailed records within their minutes of those who attended meetings and held positions within the church. A relevant example is that of Reverend R. F. Taylor, an African American minister who lived on and owned land that is now the Dallas Arboretum and Botanical Garden. He was a traveling minister, and each church that he visited created fairly thorough records of his works and visits. Religious records were not just limited to churches; most black families used Bibles to record births and deaths instead of filing that information at the county records building. Thus, in order to trace black lineages back to before public hospitals were established and accessible to people of color, researchers often look to these preserved Bibles.

Older documentation concerning an individual’s death can also provide relevant insights into the life of one’s ancestors. This includes church obituaries and information engraved on tombstones decades ago, as well as more modern cemetery websites where such documentation has become digitized and readily available to anyone with an internet connection. The challenge is that some of these older records never had the opportunity to become digitized and preserved; for example, the Warren Angus Ferris Cemetery, established in 1847 and awarded a Texas Historical Commission marker, has been so vandalized that only one gravestone remained by 1970.

Whether it’s a census, a military record, a church record, a Bible, or a gravestone, these artifacts and physical documents created during the tumultuous Civil War and the prejudiced eras which followed have often been lost to history, taking the ancestral information documented within them into the shadows. This has made oral histories, which contain detailed stories that have been passed down through generations, one of the most effective and reliable tools for tracing African American lineage. Recognizing this, the US Library of Congress recorded a plethora of oral histories between 1932 and 1975 to document the lives of African Americans who had witnessed slavery, the Civil War, and life in the following decades. Both this project, “Voices Remembering Slavery: Freed People Tell Their Stories”, and various other oral history catalogs preserve a vast amount of genealogical information.

While there is still much work ahead in this journey, the growing list of tools that are being made available will allow today’s historical researchers and curious family members alike to work to bridge the gaps in African American genealogy and to restore for themselves and for all other African Americans their pride of place in the annals of history.