Atlanta’s First Woman Detective had a Secret Past

By Robert Scott Davis

DGS 2022 Writing Contest Submission: Your family’s black sheep

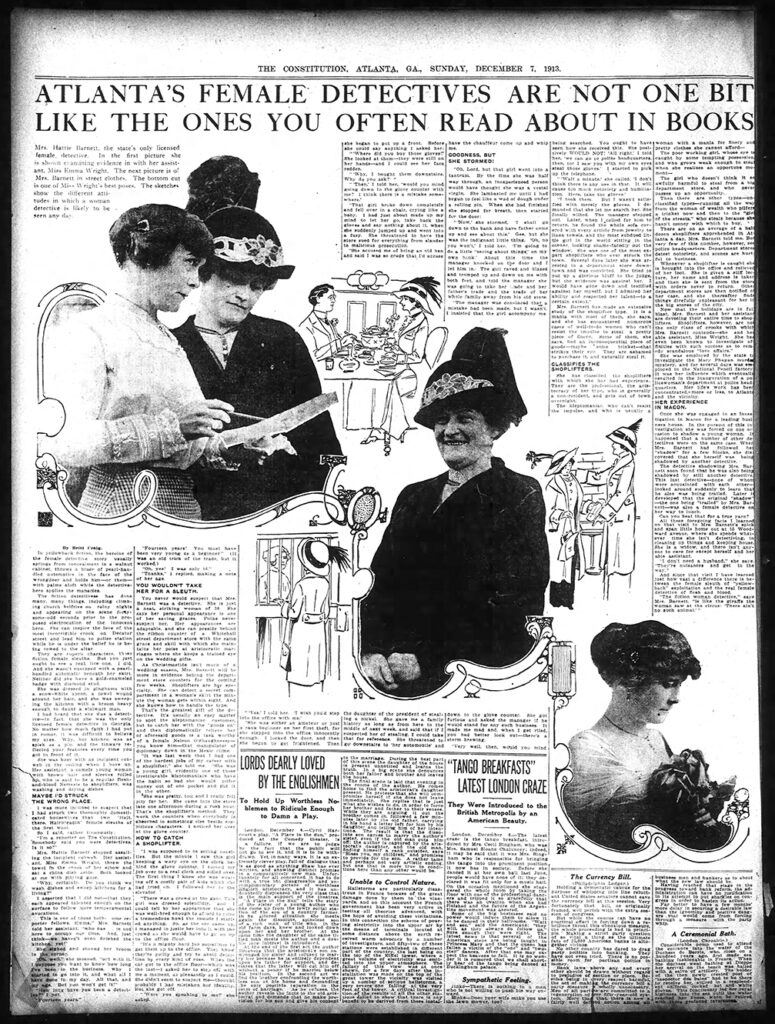

In 1909, the national media reported another first for women. The Atlanta Georgia Police Commission had approved an official detective’s license for Hattie Barnett, the first issued to a woman in that city or likely anywhere else! In the years that followed, the newspapers across the country reprinted articles on the exploits of this woman detective, including her involvement in the infamous case of the murder of Atlanta factory worker Mary Phagan.

Despite many newspaper interviews, Barnett said nothing in public about her personal life, a mystery as complicated as any crime that she helped to solve. The answer offers an explanation of her statements that she had no need for a husband to support her and that she would not take women for clients or handle divorce cases.

The hidden history of Hattie Jack Hipp began with her birth on April 23, 1868, in Tryon, Polk County, North Carolina, the daughter of John and Mary Allison Hipp. Her farmer father had served as a South Carolina artilleryman in the Civil War and reportedly died in 1892. The family lived on her grandfather David Hipp’s land in nearby Henderson County, although they went missing in the 1870 and 1880 federal censuses.1

Barnett claimed as her husband prominent locomotive engineer David Franklin Barnett, born in Hendersonville, North Carolina on August 8, 1834, and who is probably the David Barnett listed as her parents’ neighbor in the 1850 federal census. He was just shy of thirty-four years her senior.2

Hattie’s parents could have objected to more than the couple’s difference in age. David had other living wives. He had fathered at least five children with his wife Margaret Dunleavy, born in Taum, County Galway, Ireland. In the 1870 census, she was mentally ill and living in a Henderson County hospice run by Episcopal Minister R. W. Memminger. On June 2, 1879, David Barnett married Mary M. Campbell in McNairy County, Tennessee and, the following year, Henderson County officials indicted David Barnett for bigamy, although the North Carolina State Supreme Court overturned the verdict of guilty because the unlawful marriage occurred in Tennessee. (North Carolina had no jurisdiction to try a crime committed in another state.)

In the 1880 census, an enumerator listed David Barnett in Henderson County with his wife Mary M., and his son David. The couple sold property as husband and wife in January 1883, although his first wife Margaret did not die until November 1900, long after Hattie Hipp also considered him as her husband. Mary M. Campbell could not divorce David as they were not legally married and no records in Henderson County indicate that he divorced his wife Margaret.3

Hattie Hipp likely first introduced herself as Mrs. David F. Barnett sometime in the late 1880s, the period that she said that she first worked as an investigator and when federal authorities convicted David Barnett of bootlegging in Cherokee County, North Carolina. The couple likely lived in Asheville or Chattanooga before moving to Birmingham, Alabama where David died of pneumonia on January 2, 1892.4

The couple had no children and Hattie could not file for any Confederate pension benefits as the widow of a Civil War soldier, which required proof of a legally licensed marriage. She would manage boarding houses for almost the rest of her life.5

Hattie Barnett appeared as a private detective in the 1910 federal census and many times afterwards in city directories, as well as many eventful years later until her death in Atlanta on May 20, 1923. She had a reputation for catching shoplifters, including whole gangs, across the South. In her career, she also brought down burglars and confidence artists, sometimes while in disguise. Some desperate individuals made attempts on her life.6

Barnett’s notoriety was buried with her. Even her family’s genealogist had never heard of her, despite his grandmother (Barnett’s niece) having lived with the detective in Barnett’s last years. No memoirs of anyone who knew her have turned up. That she has gone forgotten, even to Atlanta’s historians, her final mystery.

Notes

1 Death certificate of Hattie Barnett, May 22, 1923, number 14116, Georgia Archives, Morrow; Hamilton C. Jones, North Carolina Reports 52 (1859-1860), 400-402; Hipp, John (Polk County), Confederate Pension Claims, North Carolina Archives, Raleigh; “In Short Meter,” Atlanta Georgian and News, September 16, 1909; “Barnett,” Atlanta (Georgia) Constitution, May 21, 1923; Henderson County, p. 273B, Seventh Census of the United States (1850) (National Archives microfilm M432 roll 634) and Polk County, North Carolina, p. 99, Eighth Census of the United States (1860) (National Archives microfilm M653, roll 910), Record Group 29 Records of the Census Bureau, National Archives and Records Administration (hereafter NARA), Washington, DC. A Mary Hipp, possibly John Hipp’s wife Mary Ellison Hipp, appears as a widow in the 1880 and 1900 federal censuses and suggests that her family had separated before then. Fairfield County, South Carolina, ED 77, sheet 241D, Tenth Census of the United States (1880) (National Archives microfilm T9, roll 1229) and Polk County, North Carolina, ED 127, sheet 8, Twelfth Census of the United States (1900) (National Archives microfilm T623, roll 1211), NARA.

2 Atlanta City Directory 1908 (Atlanta, 1908), 422; “Mrs. Hattie Barnett, Woman Detective, is Summoned by Death,” Atlanta Journal, May 21, 1923; “Some Tombstone Inscriptions from Alabama Cemeteries,” typescript, 3 vols. (Works Projects Administration, Birmingham, 1938), 1307, Southern History, Birmingham Public Library, Birmingham; Henderson County, North Carolina 222A and 273B, Seventh Census of the United States (1850) (National Archives Microfilm M432, roll 634), NARA.

3 Richland County, South Carolina, 60, Eighth Census of the United States (1860), (National Archives microfilm M653, roll 1227),Henderson County, North Carolina, 276B, 284b, Ninth Census of the United States (1870) (National Archives microfilm M593, roll 1143) and Henderson County, North Carolina, Enumeration District 98, p. 2 (273B), Tenth Census of the United States (1880) (National Archives microfilm T9, roll 967), NARA; Thomas S. Kenan, North Carolina Reports, vol. 83 (Raleigh, NC, 1880), 615-16; Margaret Payne to author, February 3, 2014, in the author’s possession; Greenville Chapter of South Carolina Genealogical Society, Greenville County, S. C. Cemetery Survey, 6 vols. (Greenville, SC, 1977-2000), 3: 94. Hattie Barnett (1868-1923), detective, should not be confused with the Miss Hattie Barnett of California who also had a complicated marriage. “A Curious Matrimonial Question,” Telegraph & Messenger (Macon, GA), November 14, 1871.

4 Atlanta City Directory 1908 (Atlanta, 1908), 422; “Atlanta’s Woman Detective Says Numerous Burglaries are Committed by Women,” Atlanta Journal, February 10, 1909; “Woman Detective to take License,” Atlanta Georgian, October 2, 1907;United States v. David Barnett, case 5489 (September 1887), Criminal Case Files, 1790-1860, Box A-E, Raleigh Term, Eastern District of North Carolina, 53A0293, National Archives at Atlanta, Morrow; Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineer’s Monthly Journal 26 (February, 1892): 176.

5 David F. Barnett served in the 17th South Carolina Infantry Regiment that surrendered at Appomattox.Richland County, South Carolina, 60, Eighth Census of the United States (1860), (National Archives microfilm M653, roll 1227) and D. F. Barnett, Compiled Service Records of Confederate Soldiers who Served in Organizations From the State of South Carolina (National Archives microfilm M267, roll 291), Record Group 109 War Department Collection of Confederate Records, NARA.

6 Atlanta City Directory 1911 (Atlanta 1910), 469; Fulton County, Georgia, ED 87, sheet 6B, Thirteenth Census of the United States (1910) (National Archives microfilm T624, roll 192), NARA; “Mrs. Hattie Barnett, Woman Detective, is Summoned by Death,” Atlanta Journal, May 21, 1923; “Services Wednesday for Mrs. H. Barnett,” Atlanta Constitution, May 22, 1923.

©2022 Robert Scott Davis

Published by Dallas Genealogical Society with the author’s permission