Out of the Attic: Boiled Sheep’s Brains and Perfect Cooking

by JoAnn Graham

My mother, Patricia Jarrett, was born in May 1924 in Isleworth, a suburb of London. She was an only child. Her father was a “bobby” – an English policeman. The little family moved to various small towns in Kent, a county southeast of London – Cranbrook, Danetree, Tonbridge and finally Deal. It was Deal where the family lived the longest, and that Patricia called her hometown, though she did not actually spend very much time there.

At the equivalent of kindergarten (age 5) she rode a public bus to a convent day school in a nearby village. (Can you imagine letting your five-year-old ride the city bus alone? But you could do it safely in 1929.) The next year, day school quickly changed to weekly boarding school, and Patricia came home only on weekends. This meant living in dormitories and eating communal meals. At about age 9, she transitioned to full time boarding school and only came home for holidays and at the end of the school terms.

My mother frequently talked of her boarding school experiences and most of them were positive memories. But one memory that she often recalled dealt with the requirement that all students eat all the food on their plates at every meal. If you did not finish your meal, you were required to sit at the table until you did, even if it meant missing classes, chores, or recreation time.

While British cuisine has many high points, the British also eat some things that Americans may find distasteful. Foremost among these often despised foods are offal – the entrails and internal organ meats of various animals. You have probably heard of haggis – an ox stomach stuffed with the heart, lungs and liver of a lamb, beef stew meat and oatmeal and then boiled for two hours. Steak and kidney pie, beef tongue, sweetbreads and tripe are all familiar ingredients in cuisines around the world, but not so familiar to those in living in the US.

Patricia enjoyed many of these dishes but she drew the line at boiled sheep’s brains. She often told us that boiled sheep’s brains were always served for Saturday morning breakfast and she simply could not eat them! She said she missed many a Saturday morning recreation time sitting in the dining room alone because she couldn’t bring herself to eat the boiled sheep’s brains. She took solace one semester when another girl could also not stomach the boiled sheep’s brains and she had company in the empty dining room.

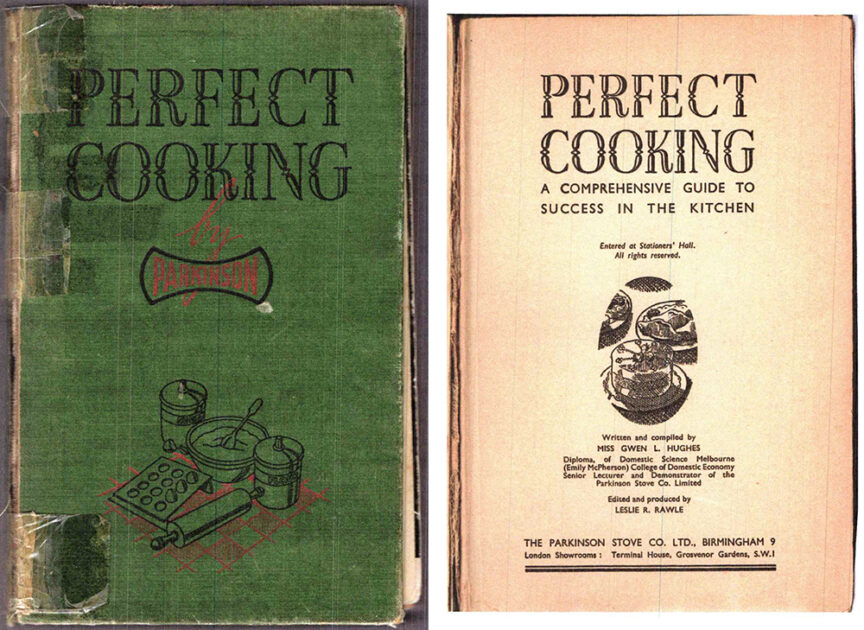

Knowing my mother’s love of cooking and some of the delicious traditional recipes she often made for us, I was thrilled to find a very old and yellowed copy of a Perfect Cooking cookbook while sorting my mother’s estate. The cookbook had originally been my grandmother’s, but I remember my mother using it often. It was acquired in 1938 as part of my grandmother’s purchase of the Parkinson “Renown” Gas Cooker.

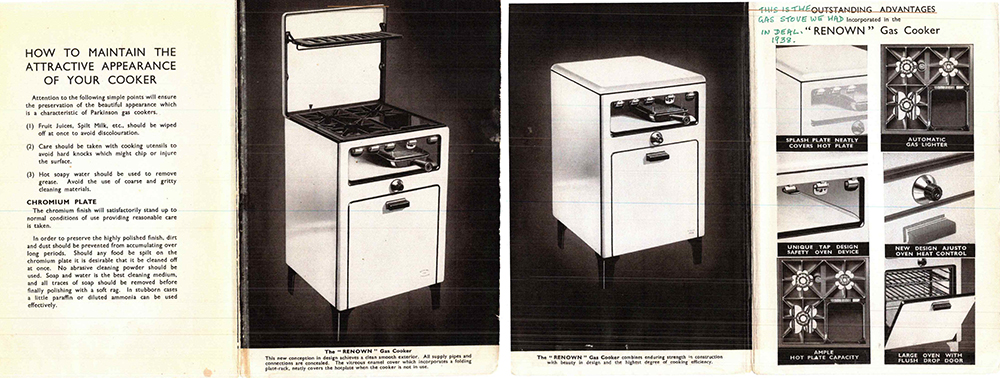

Founded in London in 1816 to make gas meters, W. Parkinson and Company went through many mergers, acquisitions and changes in its history. In February 1937, W. Parkinson and Company were exhibitors at the British Industries Fair in London. With over 1,500 exhibitors and a record-breaking area of exhibit space, the British Industries Fair was one of the largest in Europe. Buyers from over 60 countries came to see the goods for sale. The products offered included various gas cookers with features new to English kitchens. Especially impressive at the time were the company’s gas burners with pilot lights that did not require a match to light, and an adjustable temperature “Ajusto” gas oven. My grandmother was fortunate to buy one of the “Renown” cookers with these features and many others. She received it in 1938 at their home in Deal. With her new cooker, the company proudly included a copy of Perfect Cooking.

Perfect Cooking, A Comprehensive Guide to Success in the Kitchen was first published by W. Parkinson and Co in approximately 1930. All copies are undated, but publication continued into the 1970’s and reprints are available with different cover designs. How many changes were made over the years is unknown since all editions have 287 pages. Written by Gwen Hughes, a degreed domestic economist and “Senior Lecturer and Demonstrator of Parkinson Stove Co.”, the cookbook is a comprehensive guide to all manner of cooking and nutrition. How to make tea was, of course, explained in detail. Several pages are also used to explain how to provide babies and children with proper nutrition as they grow. And it had recipes for the dreaded boiled sheep’s brains!

In preparation for writing this article, I watched some YouTube videos on cooking sheep’s or lamb’s brains. Some were fried after boiling, but all were boiled. The same is true with the recipes for sheep’s brains in Perfect Cooking. And from my mother’s descriptions, it seems that the convent cooks just did the boiling and not much more. I have to say that I don’t think I would be a fan of boiled sheep’s brains, either.

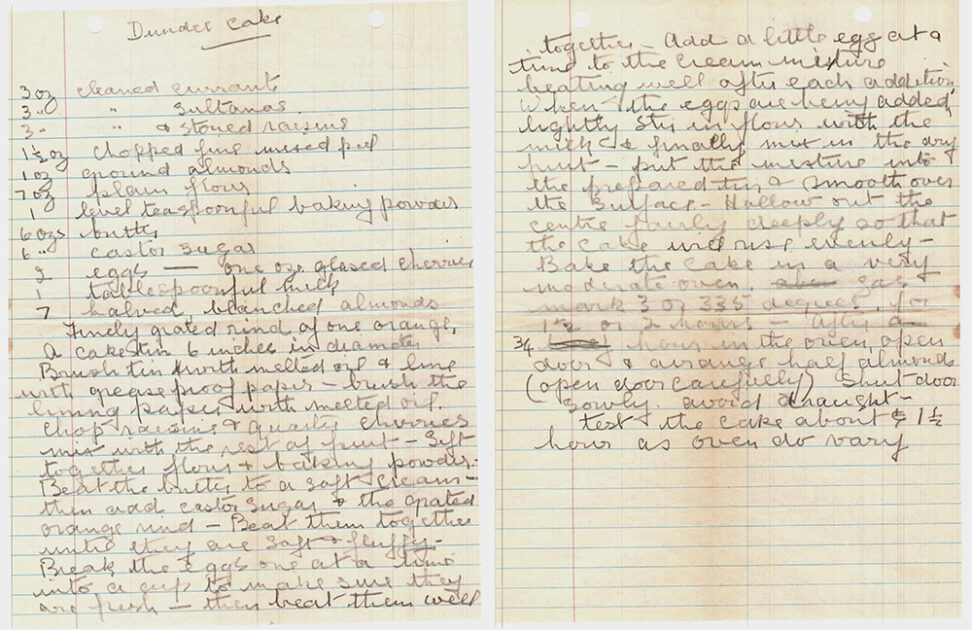

But the best and most important part of finding this old cookbook are the handwritten recipes from my mother and grandmother that are tucked inside the pages of Perfect Cooking. “War Pudding” from my mother reflects the challenges British cooks faced during World War II, as severe rationing and shortages made many ingredients very difficult to find. Some recipes, like my grandmother’s Dundee Cake reflect her Irish heritage and were family traditions throughout my life. The directions, terminology and ingredients reflect the foods and methods used at the time. My copy of Perfect Cooking is literally falling apart, with yellowed cellophane tape now failing to hold the spine together. Many of the very loose pages have notes in the margins and on the recipes. There are over a dozen recipes handwritten by my mother and grandmother, folded and placed inside the book. The book has traveled far in almost 100 years. From its original home in England, it moved to Seattle, Germany, Albuquerque, Colorado, and finally Texas. But all that time it was a reliable provider of good meals in the place called home by three generations of my family. It will soon pass to my son, a talented home chef and the fourth generation to cherish this treasure.